Foreword

Vectors are the core mathematical tool hiding inside the ray tracing algorithm. They allow us to describe relations in 3 dimensional space.

In this blog post I will describe all of the needed vector operations that will be used in GoRay.

You can view the full code for this post here

Vector representation in Go

First thing I need to do, is define how vectors will be represented in the code. I’m coming from a highly object oriented language (ruby), so naturally I picked a thing that ressembles objects the most - struct (this may not be the Go way, so if You have any other propositions, please ping me).

So let’s define a struct that will represent a 3 dimensional vector with coordinates (x, y, z):

package core

import "math"

// Vector - struct holding X Y Z values of a 3D vector

type Vector struct {

X, Y, Z float64

}

Note that the struct’s name and all of the coordinates are written in capital letters. That’s because in Go, only stuff that’s written in capital letters gets exported when your package is imported somewhere. Lowercase functions, structs, etc. are available only inside the package. If you want some more information about this, visit this link

Operations on vectors

Go allows us to define methods on structs, which seems like a perfect candidate for defining all of the needed vector operations. Methods are plain Go functions, but they are defined with a receiver that comes before the function name.

We can define a method on a receiver in two ways:

- Pointer receiver

func (a *Vector) Add(b Vector) Vector {

a.X += b.X

a.Y += b.Y

a.Z += b.Z

return a

}

- Value receiver

func (a Vector) Add(b Vector) Vector {

a.X += b.X

a.Y += b.Y

a.Z += b.Z

return a

}

The core difference between these two is that, the one that is defined on a pointer receiver, will mutate the actual object it was called on. Analogically a method called on a value receiver will not mutate the receiver, because it will operate on a copy of the original receiver.

All of the methods that will be presented in this post are defined on a value receiver. A new Vector will be returned where applicable.

This type of notation allows for a verbose representation of the equations used in the ray tracing algorithm.

With the technicalities out of the way, let’s move on to implementing the actual vector operations.

Adding two vectors

This operation is achieved by adding the corresponding coefficients of two vectors together.

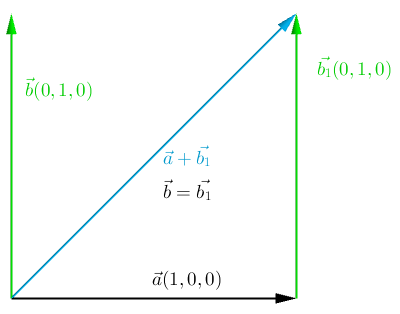

Geometrically it looks like this:

func (a Vector) Add(b Vector) Vector {

return Vector{

X: a.X + b.X,

Y: a.Y + b.Y,

Z: a.Z + b.Z,

}

}

func TestAdd(t *testing.T) {

result := Vector{1., 1., 1.}.Add(Vector{2., 2., 2.})

assert.Equal(t, Vector{3., 3., 3.}, result, "should add correctly")

}

Subtracting two vectors

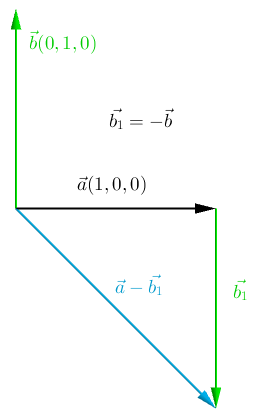

Subtraction is similar to addition, with the difference that we add a negated vector:

Analogically to addition of two vectors, we subtract the corresponding coefficients of two vectors:

func (a Vector) Sub(b Vector) Vector {

return Vector{

X: a.X - b.X,

Y: a.Y - b.Y,

Z: a.Z - b.Z,

}

}

func TestSub(t *testing.T) {

result := Vector{3., 3., 3.}.Sub(Vector{1., 1., 1.})

assert.Equal(t, Vector{2., 2., 2.}, result, "should subtract correcly")

}

Multiplying vector by scalar

Multiplying by a scalar can be interpreted as scaling the vector (modifying it’s length). This operation is also pretty straightforward, as we have to multiply each coefficient by the scalar:

func (a Vector) MultiplyByScalar(s float64) Vector {

return Vector{

X: a.X * s,

Y: a.Y * s,

Z: a.Z * s,

}

}

func TestMultiplyByScalar(t *testing.T) {

result := Vector{3., 3., 3.}.MultiplyByScalar(2.)

assert.Equal(t, Vector{6., 6., 6.}, result,

"should multiply each component by given scalar")

}

As a bonus, we also get division by a scalar, by multiplying by 1/s

Dot product of two vectors

The dot product is the first operation that doesn’t return a Vector. It returns a scalar value of type float64.

This operation is particurarly important in the context of the ray tracing algorithm, because of it’s common use in the equations.

It’s algebraic definition is the following:

It’s a simple equation, we multiply corresponding coefficients of both vectors, and then sum those multiplications. But this definition isn’t of much use in context of the ray tracing algorithm. What we need here is the geometric definition:

The notation ||A|| means length of vector A (more on that in a sec). θ is the angle between the vectors. The fact that we use the cosine function gives us some interesting cases:

When the vectors are orthogonal, then the angle between them is 90°. This means that the cosine is 0 and the whole dot product is 0

When the vectors are codirectional, then the angle between them is 0°. This means that the cosine is 1 and the dot product evaluates to:

This two cases give us a way to determine if two rays are orthogonal or codirectional, which has a huge meaning when evaluating materials of objects.

With the theoretical stuff out of the way, let’s proceed with the implementation:

func (a Vector) Dot(b Vector) float64 {

return a.X*b.X + a.Y*b.Y + a.Z*b.Z

}

func TestDotProductOfTwoPerpendicularVectors(t *testing.T) {

result := Vector{1., 0., 0.}.Dot(Vector{0., 1., 0.})

assert.Equal(t, 0., result, "dot product of two perpendicular vectors is 0")

}

func TestDotProductOfTwoParallelVectors(t *testing.T) {

result := Vector{1., 0., 0.}.Dot(Vector{1., 0., 0.})

assert.Equal(t, 1., result, "dot product of two parallel vectors is 1")

}

Pretty simple, eh?

Length of a vector

As stated earlier, we denote the length of a vector A like this - ||A||. It’s algebraic definition is following:

As you can see, it’s basically a dot product of a vector with itself, under a square root.

So we can use the already implemented Dot method, to implement this one:

func (a Vector) Length() float64 {

return math.Sqrt(a.Dot(a))

}

func TestLength(t *testing.T) {

assert.Equal(t, 3., Vector{3., 0., 0.}.Length(),

"calculates the length(magnitude) correctly for Vector{3., 0., 0.}")

assert.Equal(t, 6., Vector{6., 0., 0.}.Length(),

"calculates the length(magnitude) correctly for Vector{6., 0., 0.}")

assert.Equal(t, 6.324555320336759, Vector{6., 2., 0.}.Length(),

"calculates the length(magnitude) correctly for Vector{6., 2., 0.}")

}

Cross product of two vectors

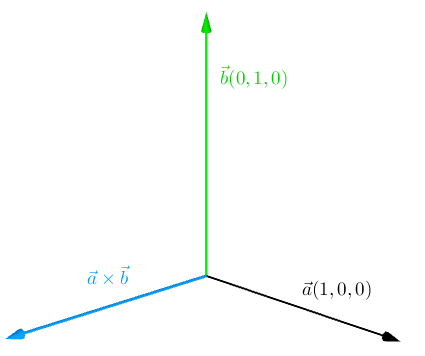

Unlike the dot product, the cross product returns a new vector, that is perpendicular to the other two. Additionally this operation is defined in R3.

The cross product can be also used for calculating a surface normal (the surface that is defined by the two vectors).

The cross product formula is somewhat hard to remember:

The implementation looks like this:

func (a Vector) Cross(b Vector) Vector {

return Vector{

X: a.Y*b.Z - a.Z*b.Y,

Y: a.Z*b.X - a.X*b.Z,

Z: a.X*b.Y - a.Y*b.X,

}

}

func TestCrossProduct(t *testing.T) {

result := Vector{1., 0., 0.}.Cross(Vector{0., 1., 0.})

assert.Equal(t, Vector{0., 0., 1.}, result,

"cross product returns a vector perpendicular to the other two")

}

Normalizing a vector

Also called calculating a unit vector - versor:

All we have to do, is divide (multiply by 1 / x) each of the vectors components by the length of the vector:

func (a Vector) Normalize() Vector {

return a.MultiplyByScalar(1. / a.Length())

}

func TestNormalize(t *testing.T) {

assert.Equal(t, Vector{1., 0., 0.}, Vector{10., 0., 0.}.Normalize(),

"returns a unit vector (versor) from the given vector")

assert.Equal(t, Vector{0., 1., 0.}, Vector{0., 10., 0.}.Normalize(),

"returns a unit vector (versor) from the given vector")

assert.Equal(t, Vector{0., 0., 1.}, Vector{0., 0., 10.}.Normalize(),

"returns a unit vector (versor) from the given vector")

}

Summary

Now that we have the basic math implemented, we will move to the more exciting stuff. Stay tuned.

comments powered by Disqus